The Pennsylvania Superior Court has dropped a bombshell on the state’s mandatory minimum sentencing statutes. On August 20, 2014, the court announced that a 5 year mandatory sentence imposed for possession with intent to deliver where a firearm was in the vicinity was unconstitutional. The court’s decision found unconstitutional a sentencing law that only required the fact that a gun was in “close proximity” to the drug sales be proved to a judge at sentencing by a preponderance of the evidence rather than to a jury beyond a reasonable doubt.

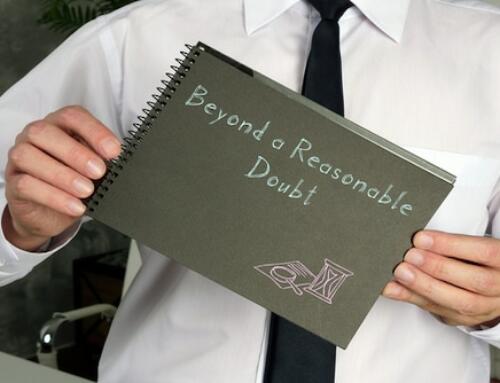

Late last year, the United States Supreme Court held, in Alleyne vs. United States, 133 S.Ct. 2151 (2013), a similar federal mandatory minimum statute unconstitutional for the same reason. The Supreme Court’s very sound rationale was that if a fact (ie. the weight of the drugs, whether a gun was nearby or if the sales occurred in a school zone) triggered an additional penalty, then that fact must be proven to a jury beyond a reasonable doubt as the sentencing statute created a “new aggravated crime”. In other words, if the prosecution is going to seek an increased penalty with a mandatory minimum, then it must prove every fact that will increase the punishment at trial beyond a reasonable doubt.

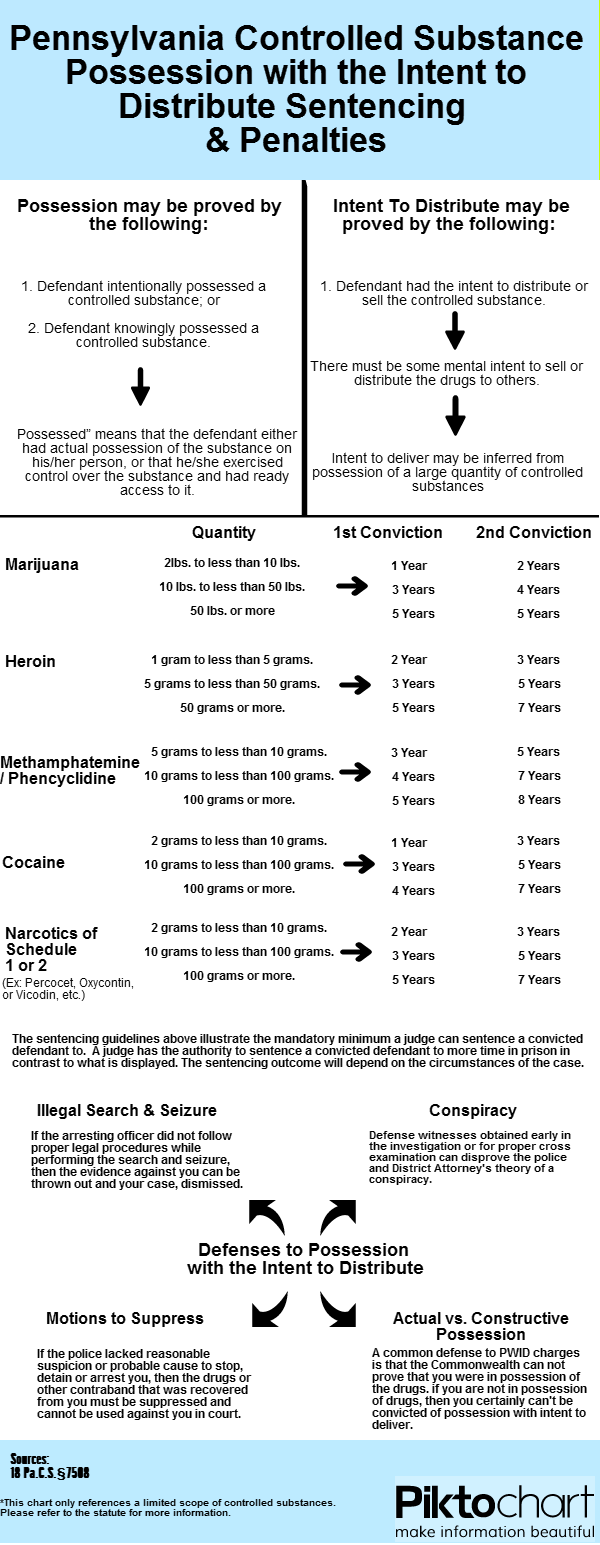

Since Alleyne was announced, Common Pleas court judges across Pennsylvania have been split over whether similar state sentencing statutes are constitutional. Most of these mandatory minimum statutes deal with possession with intent to deliver charges. These mandatories most often involve the weight of the drugs, as illustrated in the below infographic, whether the drugs were possessed in a school zone or whether there was a gun in close proximity to the drug sales. Many judges found that the state laws were still constitutional as the portion invalidated by Alleyne could simply be severed from the rest of the statute and the laws’ intent carried out. For example, the District drug crime lawyer in Philadelphia began requesting that jurors answer certain questions on Verdict Sheets if they made a determination of guilt on the charge of possession with intent to deliver. Many judges would agree and allow the jury to answer questions such as, “If you find the defendant guilty of possession with intent to deliver, do you find beyond a reasonable doubt that he possessed 14.2 grams of crack cocaine beyond a reasonable doubt?” Or, “If you find the defendant guilty of possession with intent to deliver, do you find that a gun was in close proximity to the possession with intent to deliver?”

The prosecution and court’s rationale was that if the jury found, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the fact triggering the mandatory sentence existed then the court could impose the mandatory minimum and any portion of the statute that ran afoul of Alleyne could be severed.

The Superior Court of Pennsylvania changed all of that on August 20, 2014. But, they even went a step further to provide relief to those who had previously been sentenced under these mandatory minimums.

In Commonwealth v. Newman, 2014 Pa.Super. 178, the Superior Court held that (1) the five to ten year mandatory minimum sentence required when convicted of possession with intent to deliver while a firearm was in close proximity under 42 Pa.C.S 9712.1 was unconstitutional under Alleyne and, perhaps, more importantly (2) the new rule announced in Alleyne was to apply retroactively to those sentenced before the now-unconstitutional sentencing scheme. Therefore, those that were sentenced to mandatory minimums that have now been deemed unconstitutional may be entitled to relief in the way of a new sentencing hearing by filing a PCRA petition with the trial court or a direct appeal with the Superior Court.

The Newman case originated out of Montgomery County where Newman was observed making numerous drug sales out of his apartment in Glenside, PA. Once police had sufficient probable cause to obtain a warrant for Newman’s apartment, a search warrant was executed. In the bedroom, police found drug paraphernalia, specifically scales and unused baggies, a firearm and bullets. Across the hall in the bathroom, over 60 grams of crack cocaine was found. After trial, the defense sought to have Newman sentenced without the mandatory minimum required under 42 Pa.C.S. 9712.1, often simply referred to as the “gun and drug mando”. The court rejected that argument and sentenced Newman to 5 to 15 years of state incarceration. Remember, mandatory minimums are a floor, not a ceiling. Therefore, a judge is required to sentence a defendant to at least the minimum but can sentence him to more. In this case, while not increasing the lower portion of the sentence, the judge did tack on additional years of parole.

Newman appealed his sentence as illegal under the theory that the mandatory minimum statute was unconstitutional. The Superior Court agreed, vacated his sentence and remanded the matter for a new sentencing hearing without imposition of the mandatory. But, in a more sweeping ruling, the court not only held 9712.1 unconstitutional but it also stated that anyone who had been sentenced under this statute in the past may seek review of their sentence on direct appeal or through the filing of a PCRA.

All watching this case are certain that the Montgomery County District Attorney’s Office will file an appeal to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. It also makes sense that the state’s highest court will accept review of the case (referred to as “granting allocator”) as this issue effects not only the constitutionality of 9712.1 but other mandatory minimum sentencing statutes that have been effected by Alleyne. Additionally, don’t be surprised if Pennsylvania legislators begin work on re-writing these statutes to pass constitutional muster.

My observations in court since the Newman opinion was announced is that while this ruling greatly benefits defendants facing these mandatories, judges and prosecutors are not necessarily opposed to the ruling either. Why? Because in Philadelphia where the criminal dockets are clogged with drug cases involving mandatories, defendants feel they don’t have much to lose by going to trial as the mandatory often well exceeds the guidelines. But, if they can enter into an open guilty plea and the judge is given great latitude to take into account the defendant’s lack of a prior record and other mitigating factors, they will often receive a much lower sentence. Judges like to have this power and discretion without being hamstrung by the mandatories. Prosecutors also don’t seem to be complaining as it clears their caseload to focus on shootings, armed robberies, sexual assaults and other violent offenses rather than deal strictly with drug cases. The initial idea behind mandatory minimums was to create uniformity in sentencing so all were theoretically treated similarly for similar crimes. Unfortunately, every case and every defendant is different and the judge should be trusted with the ability to craft a sentence that fits the crime and the criminal.

This may be one further opportunity to demonstrate that the War on Drugs has failed and it is time to stop overcrowding our nation’s prisons with non-violent drug offenders and focus on rehabilitation and education for these individuals. If you have been charged with possession with intent to deliver drugs where the government is seeking imposition of a mandatory minimum sentence or you know someone who was recently sentenced to a mandatory minimum sentence, we urge you to contact Philadelphia criminal defense attorney Brian M. Fishman for a free consultation.